Politics as Sensibility—On Works by Li Yongzheng

by: Lv Peng

“This sort of subjectivization is a political process of determining universal precepts: We are all equal, each having come to change the aesthetic coordinates of community. Democracy, itself, is also intermittently defined by these political subjectivizations. It is just this process which resets community perceptions. However, as if equality were not a target that needed to be continually met, but instead a set given requiring repeated validation, democracy is not a form of politics, nor is it a mode of social life. The liberation of democracy would be a re-assignation of a whole new system of coordinates regarding that which is sensible. This cannot, however, guarantee the complete removal of inequalities inherent to systems of (police) control and supervision.”

—— Jacques Rancière’s Politics of Aesthetics, by Gabriel Macht

“Death…I don’t believe in it because you’re not around to know it’s happened. I can’t say anything about it because I’m not prepared for it. ” ——Andy Warhol

Jacques Rancière uses a soft approach in discussing politics and sensibility, but when reading him, one can’t help but look for a point of reference, for example a specific sensibility in one specific artwork. As in correspondences between Greenberg and Pollock, Baudelaire and Manet, as well as between Nietzsche and Van Gogh; a relationship between thought and artworks continues to raise the question of representation. While perhaps not an antithetical relationship, this is certainly one of mutual arising.

We are not clear whether Li Zhongzheng has carefully read Rancière or is even familiar with the author. The artist has never insisted on ideas or narrative to drive his practice. Instead, he works in more subtle ways to bring the audience deeply into his work. Indeed, there is an overload of Chinese politics in contemporary art, an overemphasis of human rights as artworks are misread. It is as if critics who interpret Li Yongzheng’s artworks get lost in politics, unable to speak from outside this these ideological boundaries. However, if we look carefully look at the facts, perhaps we will find that the old affairs of political ideology cannot touch upon the heart of the matter. Li Yongzheng is acutely aware of this, that things in this world are not either-or. Although Carl Schmitt has urged us time and time again never to forget the difference between ourselves and our enemies, politics still declares its state of continuous emergency. The treachery of globalization is truly laughable, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

In contrast, Rancière’s discourse is useful to us precisely because of its permeable and changeable nature. It has few political precepts, thereby ‘thinking’ itself more flexibly into the essences of politics and aesthetics. Rancière’s strongest distinction is one between politics and control. Schmitt’s central tenet also admits to this distinction, though he elides the discussion on control, thereby failing to unmask politics and aesthetics as we encounter in Rancière.

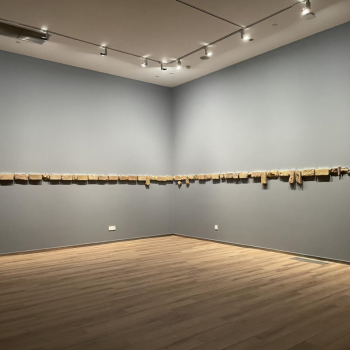

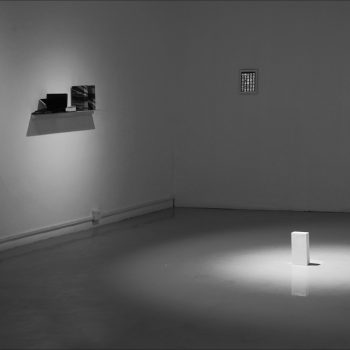

Li Yongzheng is hyper-aware, approaching artwork design through a number of channels. Firstly he surmises the spirit of an artwork’s installation site. In the history of Chinese installation art, even in global installation art, there are various degrees of emphasis upon site. Artists generally neglect site, tending instead to passively react to external factors. This is due to the public nature of installation. But Li Yongzheng thinks long and hard on his site of installation, integrating it as a key factor into the artwork, as if to turn our experience of art into one of situation.

In terms of form, the artist makes great effort to think through the material history and cultural sources of his installation artwork. Realism and tactility bring about fruition in the artist’s semiotic sphere of production, this latter being a central theme of installation or political art. Li Yongzheng refrains from purposely foregrounding this point, thereby exercising great self-restraint.

In terms of time, Li Yongzheng’s installation artworks often address the theme of dissipation. This material annihilation brings with it a certain representational structure. As the material of a work goes through the process of dissipation, it exists at the border between two system-states. One structure dissipates as the other accretes. In this way, Li Yongzheng brings us into the fold of his semiotic mythos. For example, in his artwork, Consumed Salt and Gangren Boqie Mountain, 2000 bricks of Himalayan rock salt are stacked on site, forming a representational Gangren Boqie Mountain. Through the course of the exhibition, the artist then sells these bricks of salt for 100 Chinese RMB apiece, selling 1323 bricks in the span of one month. In all, these rock-salt bricks underwent a dual dissipation. Firstly, they were taken from Gangren Boqi Mountain and disengaged from their natural locus. Secondly, these bricks then underwent a second dissipation, disengaged by the artist from the installed artwork, taken apart from their signifying unity comprising Gangren Boqie Mountain, annihilated as the signified mountain ceased to exist. At the same time, however, the artwork was brought doubly into being. Firstly, it was that which was signified, being Gangren Boqie Mountain and its implied background. Secondly, the artwork instituted an economic exchange, hinting at our power as consumers to dissemble a given semiotic system, while at the same time dissembling material nature, itself. However, the artist refrains from explaining Gangren Boqie Mountain as a signifier, leaving his audience to surmise its import. This catapults his artwork into an ambiguous region and returns the artwork to Rancière’s structure, wherein we discern what can be perceived in an artwork, and what cannot. Ultimately dissipation becomes a generative force in the artist’s creative process, creating material evidence and historical representation as concepts emerge from a sphere of imagination.

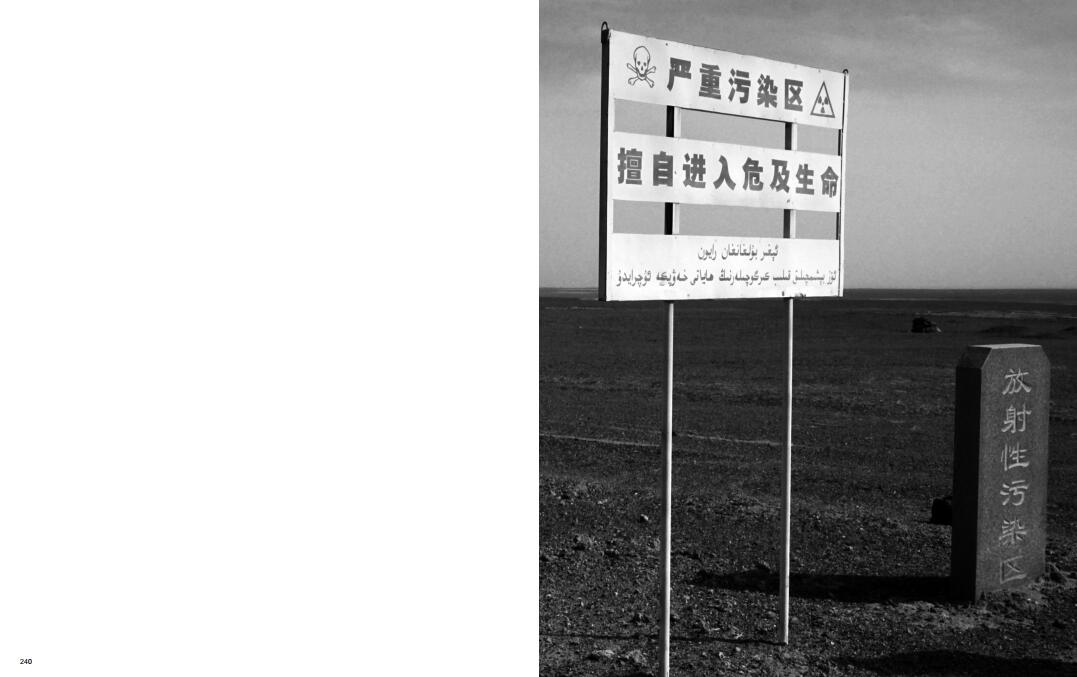

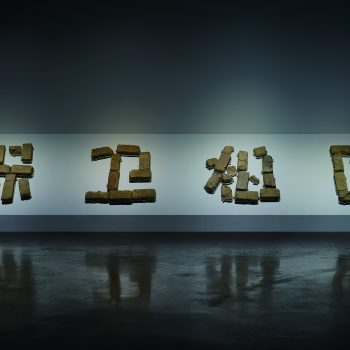

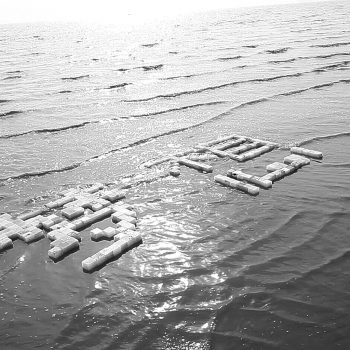

In a separate artwork, Death Has Been My Dream for a Long Time, Li Yongzheng’s Himalayan salt bricks continue their disintegration. These bricks travel all the way from the Himalayas to Tanggu harbor along China’s seaboard, just east of Tainjin. They are then arranged along the shoreline in the formation of 8 Chinese characters that say “Death Has Been My Dream for a Long Time”. In the lapping of tidal waters, these bricks then dissolve into the sea. We can read this piece as an attempt by the artist to embrace two separate instances of annihilation, fusing them into a single larger inter-textual dissipation. The process of rinsing and dissolving is not evident, but what is clear is the artist seeking to link two examples of one process together into a single representative structure, an expression of endless proliferations of what gets lost.

As a variation on annihilation, displacement is then used in another similar artwork. In terms of historical, site-specific or semiotic bricks being displaced, this displacement is actually already from the beginning visible, already gradually dissipating into a renewed sensibility. However at the same time, the internal structure of a given set of sensibilities is already being destroyed in this sense from the beginning. As soon as this system has been replicated in the process of displacement, in actuality it is already changing its sensibilities all over again. This is what Rancière calls the mode of ‘subjectivization’, where one disrupts established settings of sensibilities in this very way. From this we can see that Li Yongzheng has streak of idealism woven through his sorrow.

As we come to know this process of subjectivization, we see that displacement occupies an important place in the artist’s body of work. One can also see in many of his pieces that the artist is interested in participation. This sort of participation has been constructed through displacement on subtle structural levels. For example, the artist may invite participants to exchange one of their secrets for a fragment of one of his painted canvases, or he may invite them to participate in transmitting a specific object. Perhaps Li Yongzheng realizes that the transmission of a material object provides conditions for a re-apperception, a coming to know a material object in a new way, one oriented around the object’s removal. This is displacement in its broadened sense.

Regardless of whether what is transmitted is a material object or a meme of information, Li Yongzheng expresses an inclination towards relational aesthetics. In many instances, installation is not a key component of his installation works but rather merely a single phase along a string of relationships, a segue into a symbolic order as what can be received by the viewer.

Now we approach Li Yongzheng’s creative production from another angle. We all know that contemporary art tends to obfuscate conceptual and linguistic practises. In this sort of situation, even Rancière’s philosophical points of view can be obscured. Critics and artists can use facts and descriptions of factual objects in forming discourse. As such, what emerges from an experimental field of discourse can seem full of vitality, capable of speaking to the reader. In talking about Send for You, perhaps plain-speak alone is capable of astonishing us. In this artwork, Li Yongzheng uses an old printing machine to reproduce a few back issues of the Xinhua Daily Newspaper, once broadly distributed throughout China, from between the years of 1938 and 1947. The news content shocks people, bringing them back to an unthinkable time and space. This requires from the audience member a historical awareness, much as basic knowledge of art would be expected from any audience present at an exhibition. The crux of the matter is that the newspaper being held in our hand is not a discarded thing of the past. The information in these pages is immediately relevant even today. One can’t pretend to have not seen, nor pretend that this newspaper is an object of the past. It is not, as once semiotic content reaches into its new and contemporary context, its significance is reignited. Quatrains of all eternity may be poetic, but the questions and issues they address are not. What has been sent for you is not an old disused newspaper, but a set of real questions posed, and audience members are forced to answer. It’s fine not to engage with Rancière’s discourse in doing so, and one can still choose to run and hide. Is this not what Wittgenstein termed ‘remaining silent’? Even if one is scared witless, one must acknowledge the astonishing nature of the artwork, Send for You. In China, there are too many people, and I’m talking about artists afraid of these questions or who lack interest. (As if I am interested in protecting their good name.) They fiddle with abstractions, as arrogant philosophers who look disdainfully upon a local storyteller who is speaking many truths, giving us insight into crucial issues. We can’t say that a given philosophical viewpoint has no value, but if we take many of these viewpoints and stuff them into a single space, they will merely make a spectacle of themselves. In this manner, it is hard for people to enter into one’s philosophical thinking. It is easier for people to enter through something they see. Just as people everywhere in the city seeing boxes of goods and chicken straw cluttered around are not getting the nourishment they need to feed their inner-lives.

An artist’s semiotic silence and his ‘existential map’ are inextricably related. We are able to attain a degree of understanding while being unable to completely grasp the representational nature of Li Yongzheng’s artwork. As with another piece of his, an abstract lifeview appears to occur in a very concrete and clear manner. His original idea is always manifest in a binary structure, as with a water drop and knife’s blade, wet and dry, soft lightbeam and hard metal. These perceptions are purified, forming a primal unity. In another more complicated installation work, Metal as Medium for Water and Fire, water drips downward level by level, from the topmost and smallest metal plate, until it hits the bottommost and largest plate, upon which it is heated by a flame underneath this plate, then evaporating into steam. The artist inserts a brief explanation: “Manifest matter undergoes transformation, and in this process there is a poetic notion of death.” This piece quite clearly describes the artist’s world view of cyclical nature, where as one matter is dissipated, it comes to form another existence. Matter is never completely annihilated. This is a very Eastern notion, and the artist no doubt uses it to engage with politics as sensibility. It is just this basic mechanism of eternal transformation which shapes Li Yongzheng’s own sensibilities about politics.

In an ideal system, politics would be defined as a good in relation to the world, in apposition to control and supervision, while at the same time involved with it. At an appropriately adjusted level, the political system would be understood as continuously changing for the good; while control would be a distinguished from the start as something in the world which assigned sensibilities, dividing the communal body into distinct groups, each with their social position, modes of being and functions. In the artwork, Look! Look!, Li Yongzheng attempts to use meta-philosophy to question the whole of what can and can’t be seen. In the system of this artwork, all parts are equal; “The metal box is a 50 cm x 50 cm x 50 cm water-holding vessel, a perfect square. As far as I’m concerned, there are no primary or secondary elements in the work. There was no design needed. All sides are equal and compose a simple shape.” But on the other hand, the structure of our world intrinsically involves distinction and design, thus, “The edges along the upper part of the metal box are actually thinner, such that when the water completely fills the box, a slight incline can be detected. All four sides and the bottom are ground and buffed to be mirror-reflective. Viewers can look into the water and see themselves reflected back at them. It’s the kind of experience they would have every morning as they looked in the mirror.”

Just as Rancière pointed out, in an ideal political body, the only primary element would be the people or the ‘demos’. There would be no predetermined concretizations or linguistic mechanisms along the lines of ‘proletariat’, ‘poor’, or ‘minority’. The artist invokes this ideal politic within his artwork, creating a mirror-image which reflects an image still un-determined by the artist. The viewer sees what he or she wants to see.

The artist goes on to say, “The viewer sees him or herself through the water, an everyday experience of self-reflection. Look, stare, reflect…some people see peace or love, while others see horror and hatred. Some are content, others haunted. Some reach out to dialogue and are rejected, others dwell upon the dalliance of light, and yet still others merely see a material object. But regardless, each and every one of them will see the occasional bubble rise slowly to the water’s surface and burst.” The onslaught of subjectivization is thus challenged by the popping of occasional bubbles. Politics and the sum of all its perceptions are structured by this mirror-image, that image which the artist in his heart institutes as the entire visage of the social order. This social world was perhaps suggested into place by Western political powers, but it has evoked local modes of awareness and perception.

We now resort to sensibility as a mode of discussing an experiential artwork, Death Has Been My Dream for a Long Time. This artwork derives from an incident which took place on Jun 9, 2015 in Bijie, Guizhou, in Qixingguan district’s Cizhu village, where four children were found dead in their home. Without immediate family to care for them, these children had ingested fatal amounts of agricultural pesticide. The elder brother, Zhang Qigang, left a simple suicide note saying: “Thank you for your good will, I know you meant well by me, but I have to go. I once swore I would never live beyond 15 years of age. Death has been my dream of many years. Today is a new beginning!”We can imagine what Rancière or Agamben would have to say if they were privy to this news. How would those unfamiliar with China’s living experience or historical context respond to this piece of news? Do we actually believe that words like “particular” and “holism” are useful in this discussion? Coming from a vantage point of common knowledge gleaned from personal experience, do we surmise that we need some strange conceptual rubric to talk about this? Of course Duchamp would never want to realistically narrate events, nor would any adherent of conceptual thought and logic. It’s all really decided by our own inner value system and point of view. We don’t choose our vocabulary from the books we read. Rather, we develop our discourse according to personal need. This is the difficulty we face when making judgements about conceptual and installation art.

In talking about his artwork Look! Look!, the artist cites a phrase from the Diamond Sutra: “As a lamp, a cataract, a star in space / an illusion, a dewdrop, a bubble / a dream, a cloud, a flash of lightening / view all created things like this.” Sixth Patriarch Huizeng once used this phrase to express the impermanence and emptiness of all things. This is a complex artwork, the meaning of which gives us pause. Just as we can hardly surmise the real meaning of Huizeng’s words, we can glean from a few lines in his Platform Sutra that in the case of most perceptions, we rarely every see what is there.

Chinese artists realised in the 1980’s that they had any number of media at their creative disposal. However, looking at this age of experimentation from an art historical point of view, we must treat these questions as they occur contextually. By the end of the 1970’s, a very small piece of wood made into a ready-made artwork could grow into an emblematic representation (Wang Keping’s Silent); Huang Yongli and the Xiamen Dada group burned personal objects (often their own artworks) in a bonfire to express their casting away of traditional notions of art. Gu Wenda and Wu Shanzhuan’s multi-media practice then re-invigorated tradition and historicity as new starting points. Their artworks challenged both traditional modes of ink and wash painting, as well as the logic of Chinese characters. This was a time when artists sought to break with the past as they braved the future. In 1988, Xu Bing’s exhibition exposed the question arising after rapid modernism: Exactly what is the history of language and culture? This is really something we should think about today. Zhang Peili used repetition in his artworks to erode time, minimalizing to the greatest extent the obscuring pretension that language embodies. Of the early years, the most direct and conceptual performance artwork was Gunshot (1989) performed at the China Avant-garde Exhibition. An installation artwork expressing great wisdom, Huang Yongli took print works he had washed in a washing machine and piled them up as an installation artwork, using two historical modes of painting history to strongly foreground cultural precepts and prejudices. Yin Xiuzhen followed the traces of his own movements through a city as he then fabricated the city, telling us the story of how to ‘see’ of one’s life in urban spaces. Cai Guoqiang’s Using Straw Boats to Borrow Arrows is an apt metaphor for East-West relations. After 2000, China’s conceptual art took a turn towards to the popular, as philosophy and allusion were used to confuse and obscure, demonstrating that the structure of China’s social space is highly changeable. Regardless of what the artist wished to express, as long as medium and visual language were vague enough, the whole of society would be able to view it, as artworks passed under the censors’ radar. But how can we view the resulting exhibitions of these works? What were the artists seeking to achieve? Exhibitions these days are wholly a commercial enterprise, like small-town art fairs, merely an array of individual egos on display

Li Yongzheng is not here to discuss philosophy. He is more interested in experience. This is not to say that experience has nothing to do with philosophical method, but rather to say that experience is itself a form of contemplation. Experience is a value system, a conceptual rubric. When one drives a land rover out into the wastelands of China’s western region, one takes knowledge, experience and determination alongside. Indeed, this is a historical undertaking, a driving inquiry. God tells us that the meaning of life is the pursuit of truth. In actuality, scholars that stick with what’s popular are similar to young girls who enjoy trying on many outfits. From Derrida, Foucault, and Habermas to Deleuze, Rancière and Agamben, how will our artists and critics contextualize French, German and English notions into Chinese discourse? This is certainly something that few artists and critics have achieved.

Li Yongzheng’s value as an artist lies in his willingness to engage with the vantage point of Western art-politics, striking through the heart of contemporary Chinese sensibilities. These sensibilities as a whole comprise the most basic level of an existential map. When we laugh casually with one another, lightly discussing the differences and similarities between China and the West, we then take these intrinsically independent social worlds and cast them together. But if we are willing to cease our posturing and admit to the special nature of different experiences, of perceptions and linguistic expressions of people in Chinese society, we must then persist in making great effort to embrace the full implications of specific yet subtle perception and revealing. Then only are we ready to realize what Li Yongzheng has to offer, as he questions and redefines the practical spaces and specific structures of Western art-political notions, creating an inter-textuality with an ideal nationhood. Thereby, Li Yongzheng’s artworks are interesting insofar as they are structurally and linguistically un-utterable, as when we face his creative sentiment in the salt mountain at the end of a long narrow road. When we understand where the artist is coming from, we can read his creative process, but we are still startled by his artworks and ready-mades. Perhaps stunning us is not what Rancière originally intended, but rather he intended to produce and structure the social world. He stuns us as if by saying things could not be any other way, as he resets the structures that stand before us. Perhaps we are engulfed by this lonely aesthetic paradigm, with these complex states of mind broken open by structures of representation.

Today, as we write about art history, we are forced into authentic contemplation, forced into feeling stunned until we actually feel the tragedy embedded in the artworks before us. Between the associative nature of context and the permeability of thought; at this very point, intuition, irrationality and the power of feeling force us to feel compassion for the destiny of mankind. It is at this level that our artistic judgement rings true.

Aside from the conceptualism of Wang Jianwei, Liu Wei, and Xu Zhen, we also have Ai Weiwei, Mao Tongqiang, Li Yongzheng. These two classes of artists are similar insofar we consider the free play of materials and artistic thought. The difference lies in this: the former group intentionally or otherwise strives to maintain a vague ambiguity. The way they see it, reason is just a tacit understanding, some kind of intellectual platitude. The latter group of artists, though, have from the get-go a clear understanding of their artwork. They realize that art is the most effective mode of expression, as they have a clear intention of posing important questions to audience members willing to think, inviting us to reach a new level of understanding on these issues. If one were to ask—isn’t this just politics?—well then the answer would be simple. Chinese art today is political, but it’s a politics as sensibility, and this is exactly what we need!

Sunday, Sep 18, 2016