David Rosenberg

Li Yongzheng is an artist of large desert areas. He draws his inspiration far from the crowds, outside the walls of his studio. This results in a singular quality of expression that clashes with the codes developed by artists in large urban centers where humanity is concentrated on itself to a point of saturation.

Video maker, performer, sculptor, painter and digital network artist, Li Yongzheng displays a mixture of alchemy, shamanism and activism. When you examine his works you may sometimes think of Beuys and his dead hare, Zorio and his pentacle, Kounellis and his gas flames, Chen Zhen and ‘Social investigations’ and also Francis Alÿs and his block of ice in the streets of Mexico City. Like these artists, he recognizes that natural material has a symbolic and initiatory power. Like them, he observes the way in which the properties of material can be in resonance with those of awareness. For example, Beuys chose felt and honey. Li Yongzheng has opted for Himalayan salt and wax—two materials that are at the heart of his approach.

From the Sichuan region, the artist recounts the reality around him in a very direct manner but also sometimes in a veiled, allusive way. He starts from intimate experiences, from deep-seated feelings. Everything is exposed to the fire of inner experience. He is totally involved in the work and he invites the spectator to do likewise. Thus, when face to face with his installations you must take time to obtain information, to reflect and reconstitute for yourself the scattered pieces of a puzzle that gradually acquires form.

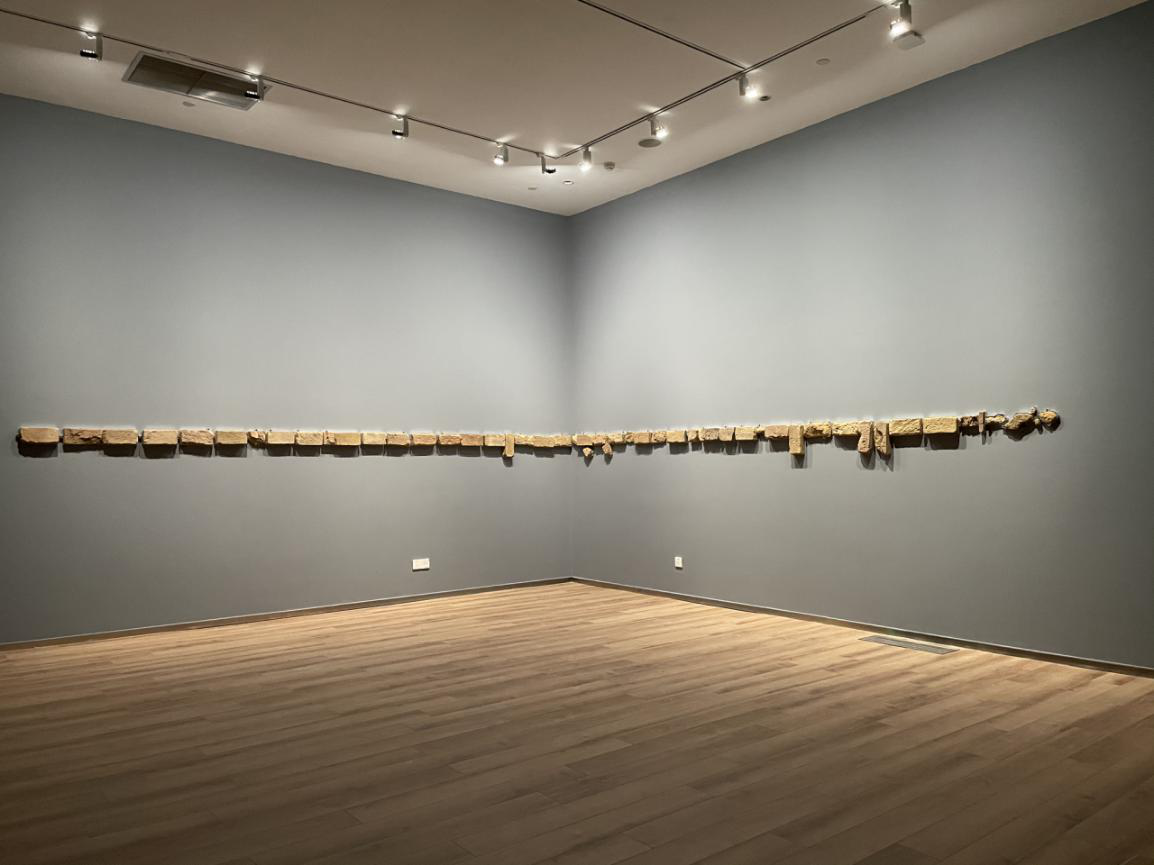

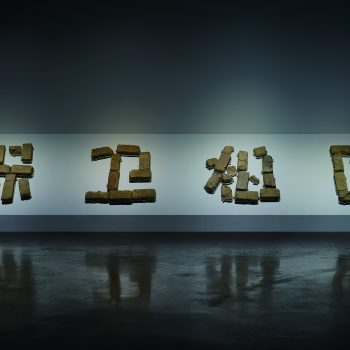

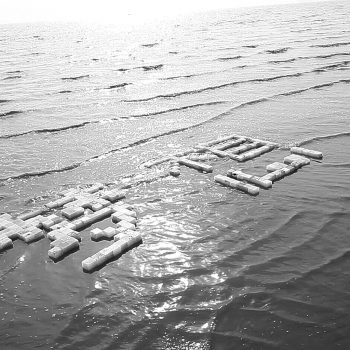

Li Yongzheng often touches on violent aspects of reality. For example, in his work ‘Death Has Been My Dream For a Long Time’ he addresses the drama of child suicides with empathy and dignity. The accidental discovery of a tragic news item in the media—the collective suicide of siblings abandoned by their parents who had gone to work in the city—was a brutal shock for the artist. He pondered, reflected and also sought information about the social context in which such a drama had occurred. Aware that no explanation would cover such an event, he chose to construct a kind of performance: a poetic and spiritual ritual in which he honored the memory of the children. He used salt bricks to write the last words of the farewell message left by the eldest child: ‘Death Has Been My Dream For a Long Time’. The artist performed the ritual on Tanggu beach near Tianjin during the rising tide. The sea covered the bricks little by little and they eventually dissolved in the water. Finally, everything disappeared, leaving just the sea and the sky. A video makes it possible to show the work in different contexts, as in a traditional exhibition space for example.

Art reflects the transitory and evanescent nature of the world around us. And what counts is less leaving a trace in matter than in our memory and awareness. Thus all his work can be seen as a long initiatory trip, a voyage to the end of the world, to the end of thought and of oneself. It is not surprising then that forms of the desert and of the sacred mountain haunt his work recurrently. They are magical places—crucibles where the spirit takes shape.

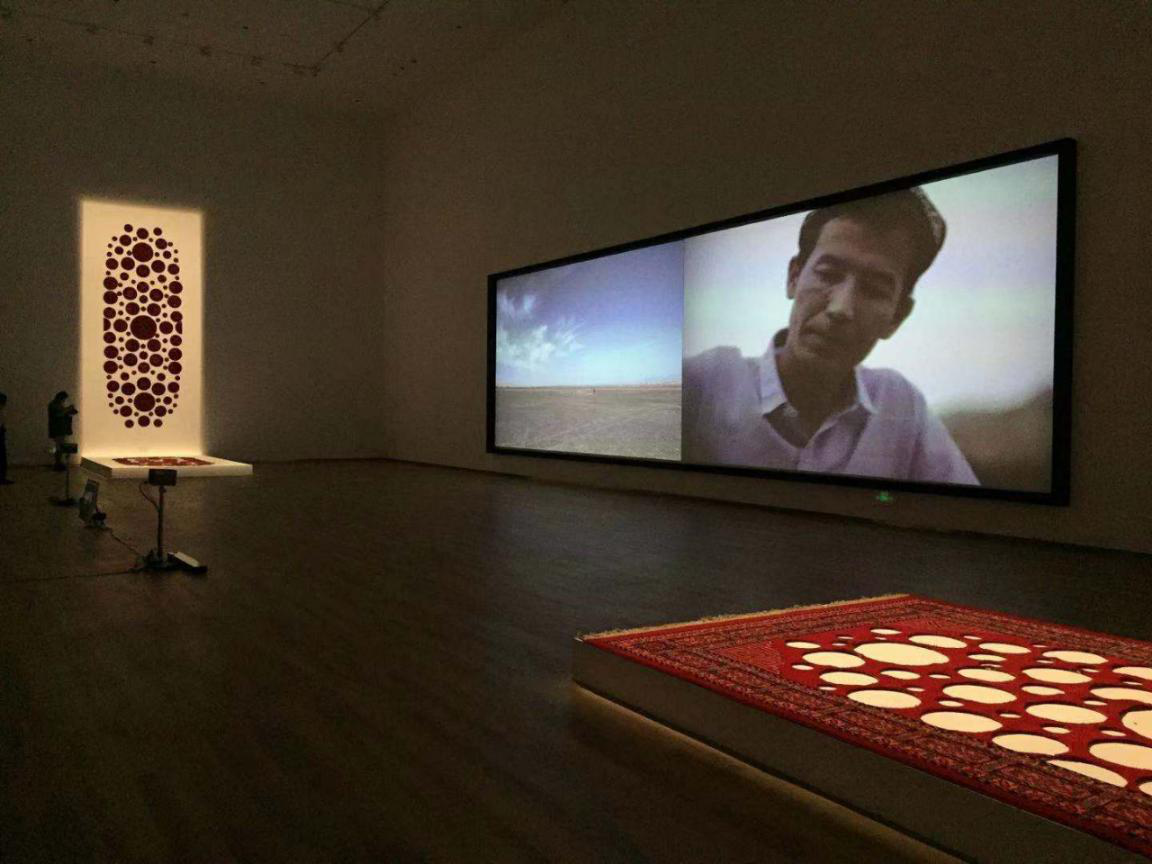

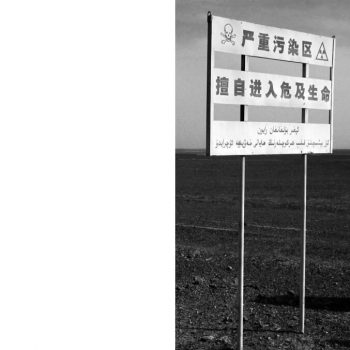

The artist brings back relics, traces, notes, souvenirs and fragments from his mental or physical travels. He piled bricks of Himalayan salt to form a mountain that then disappeared as the local public bought each brick for a ridiculously small price. He used five tons of raw salt to recreate in a gallery the form of the sacred mountain Gangren Boqi Peak in Tibet. In a desert landscape, he took a post marking the line of the frontiers of Xinjiang and then placed it on the site of a lost part of the Great Wall in the precise position of a flare that the army had used to send signals. He made a 3D scan of his body and then molded it in cement with the head replaced by a post with barbed wire wound around it. He set hundreds of laser beams pointed to the sky along the western frontier of the country. In the middle of Xinjiang desert he held a dinner with members of the Uyghur community—all this recorded on video. He grouped carpets woven by the Uyghurs and covered the patterns with wax or pierced them by laying them on pyramid-shaped points. He also used other carpets, removing all the decorative patterns by cutting them out in circles until all that was left was an empty monochrome red surface. And he then used Himalayan salt bricks to make an architectural pattern forming a swastika, on which spectators could walk without visualizing the shape on which they were moving.

The simple listing of these various actions, performances and installations shows us that the artist addresses highly topical subjects. He thus weighs each of his statements and each of his acts with care. Radical and committed, he uses a singular pathway that takes him far from Political Pop, from the acidulated recycling of the iconography and emblems of power. There is something monastic, ascetic and frugal about him, whence his attraction to simple and natural materials and also the precedence awarded to ritual and action rather than to perennial material forms generally taken by paintings or sculptures.

In this respect, his approach can also be seen together with the ‘relational aesthetics’ defined by the French critic and theorist Nicolas Bourriaud as being ‘an aesthetic of the inter-human, of the encounter, of proximity, of resisting social formatting’. We can also go a little further back in history—to the memorable exhibition designed by Harald Szeeman: ‘When attitudes become form: live in your head ‘, in which actions and thought processes outweigh finished forms and in which one-off actions substitute genre works and accepted techniques.

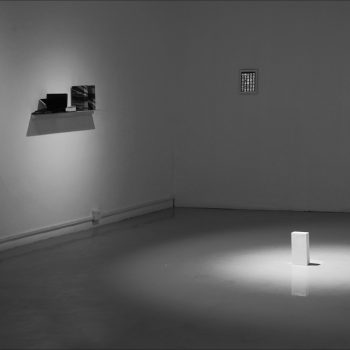

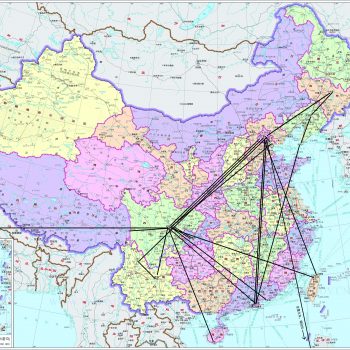

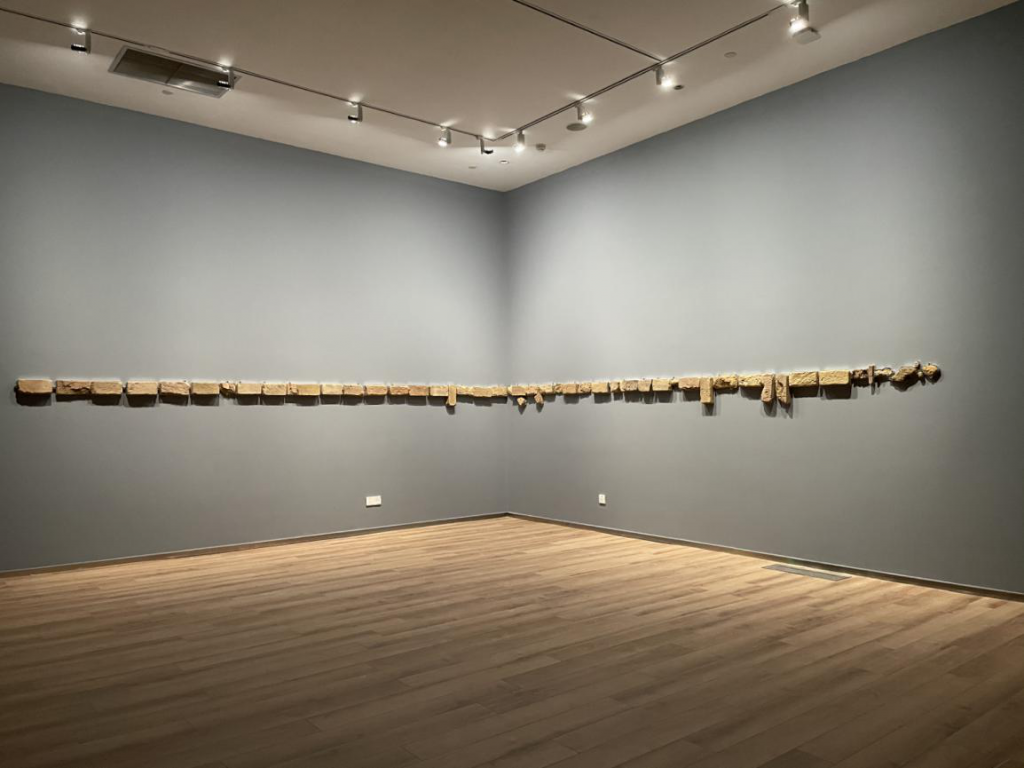

Brick Relay is a proposition that is in line with the aesthetics or philosophy that has just been mentioned. Dated ‘February 19, 2012 to present’, the work has a precise starting moment but no completion date is specified. Anyone with a little knowledge of the history of contemporary China will know that the date February 19, 2012 was not chosen at random. It refers to the public protests that occurred in the town of Wukan in the province of Guandong following massive expropriation of villagers with no financial compensation. Following the event, Li Yongzheng used the Internet to contact two people he knew who lived in the region and asked them to make two bricks using clay dug at Wukan. One of the bricks was given to a library that had been opened in the town shortly before. The artist took the other one and initiated an endless chain of correspondents via a micro-blog. He sent the brick to a first correspondent with the only instruction being that he should in turn give it to another person. The travels of the brick were traced and all the conversations and reflections stimulated by the project could be followed on the Internet. All was archived for public exhibitions and publications. Ceaselessly accumulating new contributions, Brick Relay was co-signed by all the participants. Some just received the brick and sent it without any intervention while others chose to change its appearance. For example, one of the correspondents decided to fire the brick again and cracks appeared. Then other people undertook restoration using traditional methods, such as ceramics. Only the message counted. As the artist awarded no particular importance to the brick itself, he fully accepted that it could be lost or destroyed. Likewise, he did not care whether—yes or no—this could be described as art. The main basic point was that of creating links and triggering discussion, statements and positions.

Micro-actions at a local level, the creation of communities and individual awareness … In a way, Li Yongzheng takes the opposing view to political action in the traditional sense of the term. He neither renounces utopia nor aspires to a grandiose aim to which all could be sacrificed, including the values in whose name we function. The artist holds that: “apart from the hope for a new policy, changes can only be carried out by every individual. You have to set out from your own real circumstances. Depart from trivial things, make efforts, little by little.”

Dated 2013, Free for Taking clearly illustrates this position. In an exhibition room turned into a temporary printer’s workshop, the public was invited to take facsimiles of newspapers of Kuomintang period printed on the spot. This participative operation can be linked to those created by the Thai artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, who turned certain art venues into pirate radio stations, a collective silk-screen printing studio and open canteens in which he gave soup free of charge to visitors who could sit at a table and spend a moment together. In this case, the public was present for the production in series of historically dated ‘information’ — a simple process whose main virtue is to shed new light on the present moment. The artist explained it: “I printed old issues of Xinhua Daily that were originally published in the KMT-ruled areas in the 1940s. Many articles talked about freedom and democracy, prompting many youths at that time to fight and even sacrifice their lives. These propositions are sensitive topics in society today”. It is stressed that the artist entrusted a child, a symbol of the future, with the task of handing these sheets from past newspapers to the public, like ghosts with a message for us.

In the installation “There is Salt”, the artist continued to explore the idea that the past haunts the present, that the dead have something to say to us. He spread Himalayan salt crystals on the ground, drawing a map of the Tibetan region in western China. Small stelae placed at different points of the map showed the places where persons had decided to finish their lives, taking their secrets with them. Spectators were invited to walk into the work and hear the salt crunching under their feet, as if they were walking on frost. Each person left the trace of his or her passage through this poignant memorial.

In Secret Exchanges, the artist then went towards the secrets of the men and women around him. He set up a kind of primitive economy based on exchange and barter in which he offered people he did not know to share their secrets in return for fragments of paintings that he had never shown publicly. As in Brick Relay, Li Yongzheng set up an open network to which everybody was free to make his/her contribution. The project was shown via his WeChat account and on Sina Micro-blog. Contributions could be sent directly on the Internet or by using a kind of booth in opaque glass where, unseen by others, participants could write using the computer placed at their disposal. A secret for a secret—or the art of creating links.

Using the same participative approach, the artist designed a game in which each person was invited to look for a full-size effigy of a policeman through China and then take a photo that would be shared on the networks. This approach follows on directly from the project “Do it” started by Hans-Ulrich Obrist in 1993 and in which artists from everywhere gave instructions to be followed to make a work oneself. Ostensibly ludic and ironic, the proposal inspired many people around the country and he started to receive photos from many places: sometimes a policeman was set in a flowerbed, while another was alone in the desert, and then a third stood with his feet in the snow at the top of a mountain. In a certain way the artist took the opposite approach to contemporary works showing symbols of power or oppression. Indeed, however iconoclastic or transgressive they are, they hold the spectator in the somewhat passive position of observer whereas here it is quite the opposite. If we take over and manipulate a symbol the experience will be all the more effective. Do it… yourself! Li Yongzheng is convinced that more and more people will feel this encouragement to make their own art. Here, when he is asked what he thinks the future of art will be, he replies “Professional artists will be equivalent to craftsman, creative actions will emerge in all kinds of trades and professions, and art will become a life practice for most”.

The last work by the artist to be mentioned here is Yes, Today. Between Fight Club and Larry Clarck, it assembles in a hard-hitting way all the ingredients used by Li Yongzheng: social investigation, meetings and dialogues, video recordings, the creation of an installation with a documentary part and a space where spectators are invited to join an improvised boxing fight in this case. One thinks of Arthur Cravan, a surrealist before the time, who both boxed and wrote poetry, and also the politically committed sociologist Pierre Bourdieu who stated: “sociology is a combat sport”… All began with a series of articles about teenagers from the poor areas of Chengdu and the surrounding regions. After learning the rudiments of martial arts, the adolescents participated in clandestine fights for a little money. Once the phenomenon had been made public, it seems that the authorities put a stop to it and sent the teenagers back to their families. Li Yongzheng went to meet them and asked them to talk about themselves in front of the camera, and also to repeat some of their fights, going as far as the exhibition room. When the ring was empty, two pairs of boxing gloves were made available to visitors who wished to face each other. There was no need to explain the metaphor—it smacks you in the face like a straight punch or a well-placed hook.

Art as a boxing-fight, Art as a Life Practice.

David Rosenberg

Paris, April 2021