Lan Qingwei (LQW): When you headed out from Chengdu to Lop Nor, did you know when you got there, that you’d would find the words “Defend Our Nation” spelled out in bricks?

Li Yongzheng (LYZ): I have an adventurer friend who’s been to the heartland of Lop Nor. One time, he was exploring and taking pictures when he found this sign, right in front of an old abandoned site. He said that area was named Xin Kaiping Airport, connecting the frontier Lop Nor nuclear testing site with the rest of China. Lop Nor had been a nuclear and hydrogen testing site since the 1960’s, even China’s first atomic explosion went off at that site.

LQW: How did you feel when you first saw the bricks? How was it to see them laid out like that, after so much time had passed?

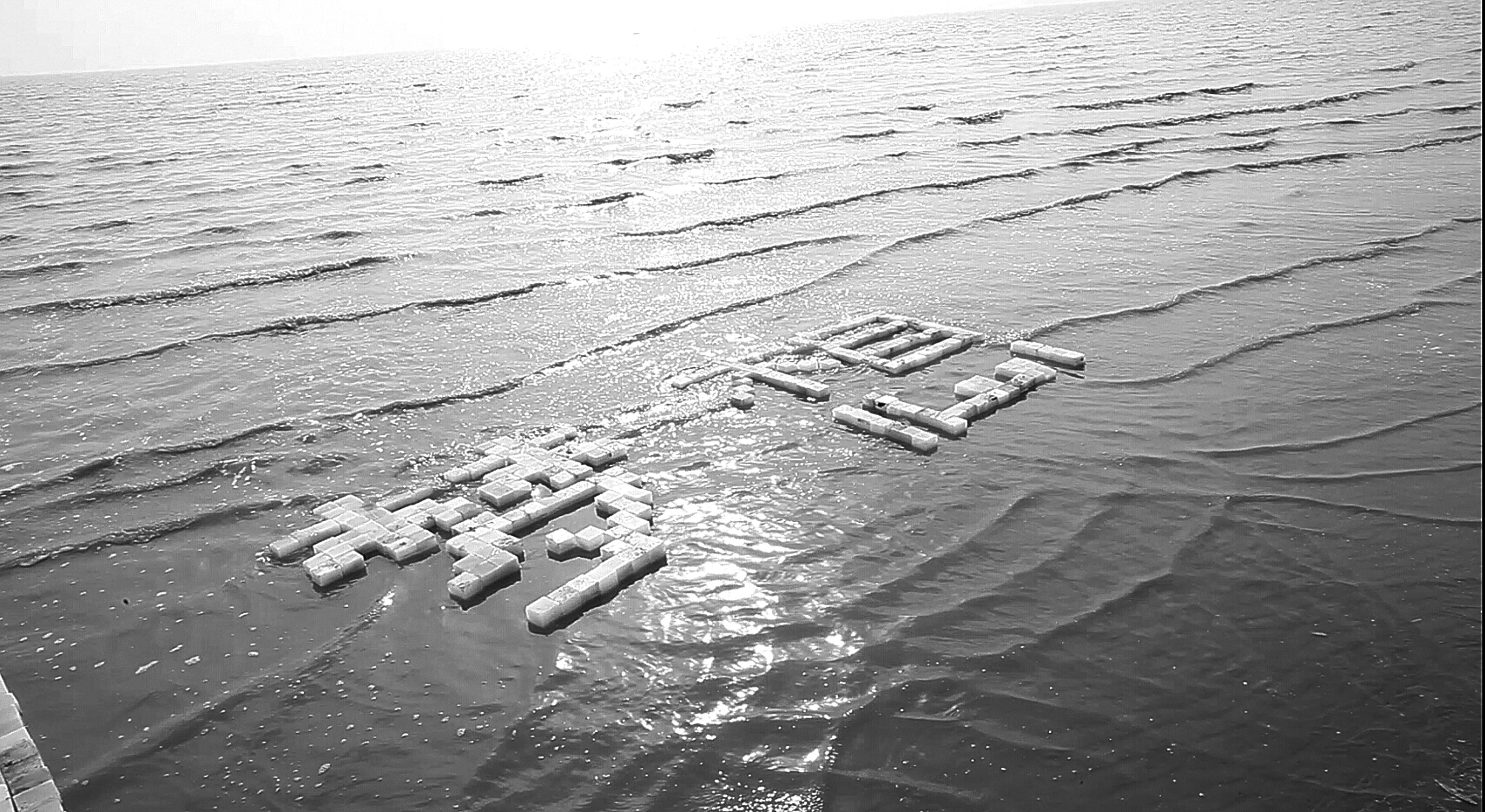

LYZ: When I set out that day from the army corps 34th regiment base and headed into no man’s land, it took until six or seven o’clock in the late afternoon until I finally saw those four Chinese words. There I was, in the setting sun, standing in front of this huge defunct and desolate military installation. It was such a cold feeling, lonely and tragic, as if I’d arrived at the end of the world, as if I were in the midst of the apocalypse, itself. After that, I came upon other defunct military areas with other billboard slogans, mostly having to do with world and human liberation.

LQW: So why did you fixate on “Defend Our Nation”, and not on other slogans?

LYZ: I felt like these specific words resonate well with what’s going on today.

LQW: Can you talk more specifically about the process of replacing the old bricks with new ones you’d brought with you? Why this “replacement”?

LYZ: I brought a slew of brand new bricks to the site and with my assistant set to work replacing all the old bricks. I also marked each of the old bricks with a code number denoting their original placement. My main reason for replacing them was that I didn’t feel comfortable just carrying bricks away. Not that anybody would ever notice or mind, but it was the principle of the thing. Replacement was how I rationalized taking those bricks.

LQW: This is not the first time you’ve used replacement in your works. It seems to be a thematic transformation of sorts, as if you are attempting to allow various elements to compose your artwork, as if you were hidden on the side lines, a witness of sorts. What’s your thinking behind this? Can you talk more about your creative process?

LYZ: In this case, replacement was a rationalization for taking the bricks away, my way of making it right. As for my audience and how they think about this replacement, what they see in it, what they think, and what they bring to the artwork; these are things I can’t control. What I haven’t anticipated is what I need most.

LQW: You’ve utilized exchange a lot in your practise, even exchanging artworks for other peoples’ personal stories. You said just now, “They’re what I need most.” What is this, really, that you need most?

LYZ: I rarely explain the thinking behind my creative process. I want my artwork be a mere starting point, toward infinity. I can’t give you any definite answer. As long as my artworks initiate open-ended lines of inquiry, open up possibilities and trajectories of thought, I’m OK. The entire meaning inheres with interaction between my audience and artwork.

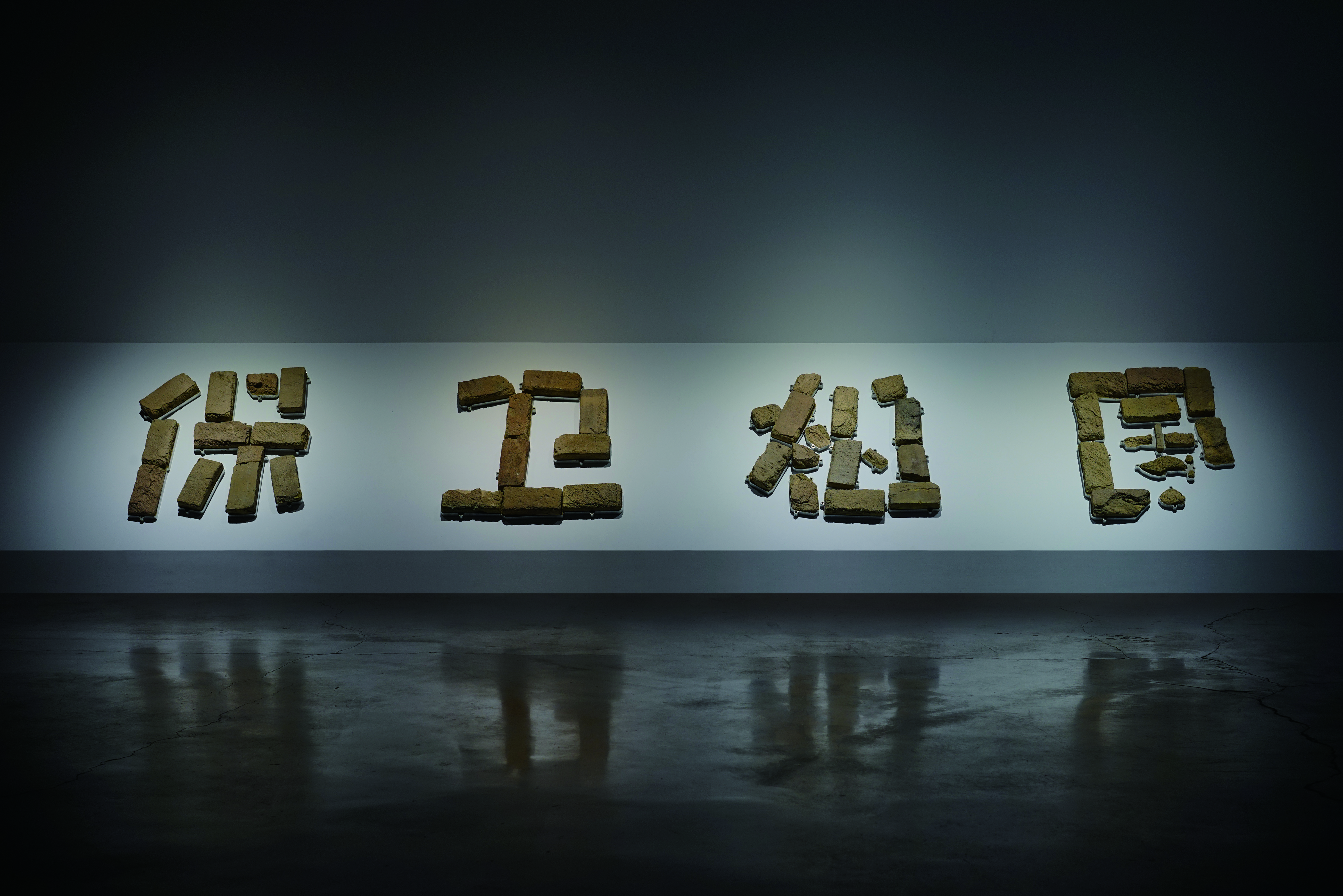

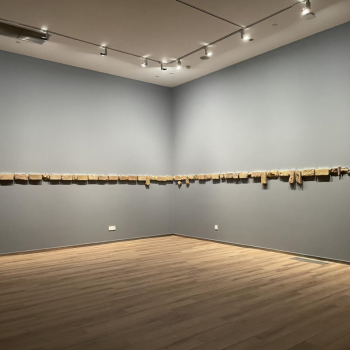

LQW: When exhibiting “Defend Our Nation”, why did you choose to display them on a metal plate?

LYZ: These bricks have taken quite a beating, weathered for years and years, and they’re brittle. Some have already broken into a number of small fragments. This was a way to set the bricks, making them easier to exhibit and transport. Or maybe it was a way to “set them in stone”.

LQW: In the video made of Defend Our Nation, your audience witnesses a natural devastation of the original site. Is this something you wanted exhibition audiences to realize? Did you think about that while filming? What steps did you take ?

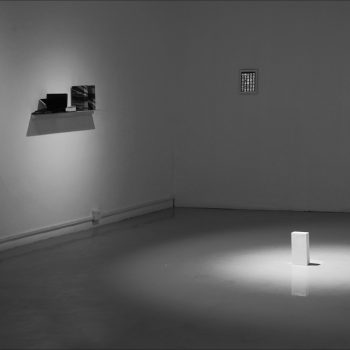

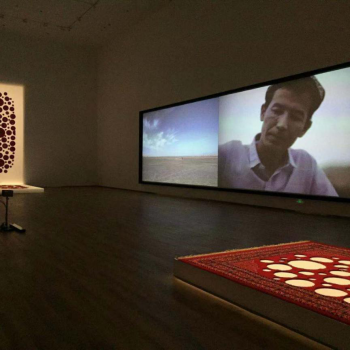

LYZ: Yes, I wanted people to see Lop Nor, this place where very few people have ever been, but have heard about. It’s a military installation in the harshest of environments, with weapons of mass destruction, huge investment of physical resources. How many people have lived there, experiencing joy and pain, anger and sadness? But now, the deathly stillness, well, it’s surreal. I made four or five videos, situating them differently per exhibition space, to give audiences to get a sense of place, changing angle and perspectives.

LQW: Lop Nor is a naturally difficult place, but it’s also an abandoned space. What Defend Our Nation conveys is a sense of contrast. Whether originally there or constructed since, can you tell me more about the historical, political, temporal, and living expression in this artwork?

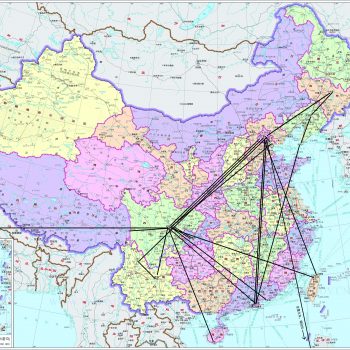

LYZ: Lop Nor is in the Uighur Autonomous region of Xinjiang, known as the Dead Sea. For a hundred thousand square kilometers around, there is not a single trace of humankind. But it’s in exactly this place that, from the time of the Great Famine in the 1950’s up through the end of the 1980’s, tens of thousands of military personnel came to invest their life and work in the building of China’s first atomic bomb. China stopped nuclear testing in the 90’s, and our military installation was forgotten about. This place used to be verdant, with growing grass and flowing water, giving rise to great civilizations. Today we can still see traces of 3000 year old sun cemeteries and river cemeteries, and ruins from Loulan, 1500 years ago an important site along the old Silk Road. It’s so hard to put into words, this feeling of place. Every word I try to use seems vapid, dead, useless in trying to describe the spectre that this place has become. What I see are the traces of the prospering and flourishing life that used to be here. I don’t see the slogans, they’re just like nuclear and hydrogen bombs, empty expressions of terror and hopelessness.

LQW: Have you considered additional ways of exhibiting this? For example, making it more of a free-standing structural work, adding to it in some meaningful way?

LYZ: I show this work differently depending on the exhibition space, especially its video component. One of the videos has this voiceover where it says, “We spent over five long hours slowly traversing a single extremely steep slope, through limitless salt marsh eroded through long years. Our tires were sliced twice, and when night had nearly fallen we saw at last a dam, so tall we could barely see the top. We drove up to it, taking a right, seeing a light flicker in the distance. This dam had been built at the edge of Lop Nor, creating a salt lake 150 square kilometers in area. Its salt water spurted up from the beneath, an emerald green turning white as ice along the lake edge. It was so surreal, such an unfeeling paradise at what seemed like the end of the earth. This was a government project site, harvesting potassium chloride.”

LQW: Did you encounter any trouble with authorities in making this artwork?

LYZ: Lop Nor is still under military command, and when you enter the region, road signs read, “Military Zone, Entry Forbidden” or “Heavy Contamination, Unauthorized Entry at One’s Own Risk”. We were met by a patrol at the edge of Lop Nor, but nothing really happened, and I entered alongside a goods inspection company. But also, driving into this area you needed a guide who was intimately familiar with the region’s topography, and you needed off-road vehicles with special equipment to deal with treacherous terrain.

LQW: Your artworks often operate on a level of simplicity, as if created through a pinhole. Your thinking is very complex, but audience sees something very simple, in some cases just a single shape, line or action. But what they perceive then refracts inwardly, giving them pause to realize in time the complexity you were alluding towards. In your eyes, would you say this artwork is relatively complicated, or not?

LYZ: It is. As you enter into this artwork, you have to know a bit about Lop Nor’s background, and you need contemporary China’s cultural context as well. For example, you need to be at least aware of the South China Seas situation, of popular opinion concerning the country’s intentions and the rising surge of Chinese peoples’ patriotism. I want to remain as simple as possible, this is a relatively sensitive topic. It’s heavy, serious and hard to talk about.

LQW: This artwork has three main components. Bricks are the first, “Defend Our Nation” is the second, and “replacement” is a third. You juxtapose these three elements and get your resulting artwork. Which would you say is the crucial and pivotal element? Would you say it was the change in environment from Lop Nor to a museum’s exhibition space?

LYZ: It’s all a part of the artwork. What’s real is what’s important. Bringing it into an exhibition space just magnifies a sense of what’s real. The artwork is merely a manifestation of this sense.

LQW: What will you do with these bricks after the exhibition? Will they be permanently displayed somewhere, or dispersed into collections? Or might they perhaps undergo another transformation, into another artwork?

LYZ: I’m not sure. Who can say anything definite about the future? We’ll have to see what spark sets off the next incarnation.

Translated by Sophia Kidd