A Very Serious Game—Beginning With Andy Warhol

—A Dialogue Between Juan Xu and Li Yongzheng

Juan Xu (J X): It’s the rules of the game that determine what art is and isn’t, and the right to decipher these rules go hand in hand with being able to talk about them. In these times, very few people are equipped to change these rules. In addition to these very few, Andy Warhol was a case all on his own. Before the 1960s, an artwork was essentially expected to be an original creation. Warhol, however, got into reproducing photos and other works, intentionally copying everyday objects and images of famous people. He appropriated consumerism and fashion, things that the art world in general had always disdained, making new rules for the game. He turned the copy into a new vehicle for artistic expression. Andy Warhol was the first to play this new art game where reproductions “displaced the original”.

Li Yongzheng (LYZ): I believe that people are products of a system, like in the Matrix. The artist is like Neo, told by Morpheus that he was an anomaly in the system. Warhol appeared at a time when the system was collapsing, and those anomalies that acted like viruses in the old system stepped right up to become the new mainstream. That’s when the rules of the game changed. There were a lot of people like Warhol in his time, but he got famous because he was good at what he did and did a lot of it. Media fixated on him, cameras flashed wherever he went.

(J X): Exactly, if it had only been a few years before or after, things would have been a lot different. A few years ago, German museums all over were doing large-scale Warhol 25 year retrospectives. Now there’s almost universal approval of Warhol. Maybe consumerism has already peaked, but progressive art techniques don’t pack the same punch anymore. Even Warhol doesn’t seem as great as he used to. In its arts critique, Die Zeit criticized him as having, in reality, no talent at all—he couldn’t write, he couldn’t paint. Strictly speaking, he wasn’t an artist. He just gave us a new way of “seeing” things, and “seeing” art is a point of departure.

(LYZ): I don’t agree with this critique. It’s much too formal a notion of ‘artist’. Warhol is a tricky topic. After WWII, it was unspeakable to talk about some absolute truth or eternal religious righteousness. Truth was hard to get a handle on. One could only fall back on oneself. Ideals were hard to talk about, like after Auschwitz, nothing was realistically feasible. These days we have to come up with some form or way to deal with difficulties and issues at hand. Now that copying and reproduction are something everyone’s equipped to do, the original that can’t be replicated is highly valued. This so-called new game isn’t really new at all. What’s rare is what’s in demand, and something old and hard to obtain is what’s new. Warhol is incredibly important, in fact too much so. We’re inundated with him, so perhaps it’s time to move on.

(JX): Right, “new” is such a relative term now, having more to do with discourse and context. This “relativity” is especially apparent in architecture. At the end of the nineteenth century, a great deal of German architecture appropriated Greek and Roman elements, so-called neo-classicism. In the nineteen-twenties, Bauhaus minimalism was a breath of fresh air for people burnt out on “faux classic” architecture. So this type of hyper-modern architecture was an extreme response to classicism, one that started a revolution in “architecture. So then time moves on, and after the 1970s, after Bauhaus’ cheap and quick building spread from America to China to take over most of the architectural world, so-called “neo-classical” architecture began to appeal to people once again. It’s just as you say, having to do with the “principle of scarcity”.

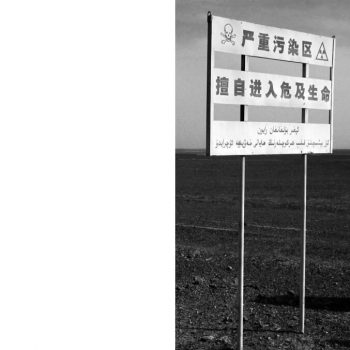

(LYZ): China’s never been a country into scarcities. It’s about authoritarian control, afraid of losing even the tiniest bit of control, whether in form or spirit. The history of Chinese art is more a solace for one’s mood, never really being a fount of new thought, not providing “scarcity”, there is no “virus” in the system. At the moment, you see some possibility on the internet, and that being said, it’s the first tool of its kind. So on Wechat and Weibo you can find some plain-speak, some naturally arising expression and language, put forth by people are innovative and creative. This is the first time we’re seeing this in sixty years. And in comparison, our society is full of artists bound by convention, with narrow frames of reference, who avoid complexity, and fail to grasp these new tools. Their creative activities have little to do with a truly creative contemporary art.

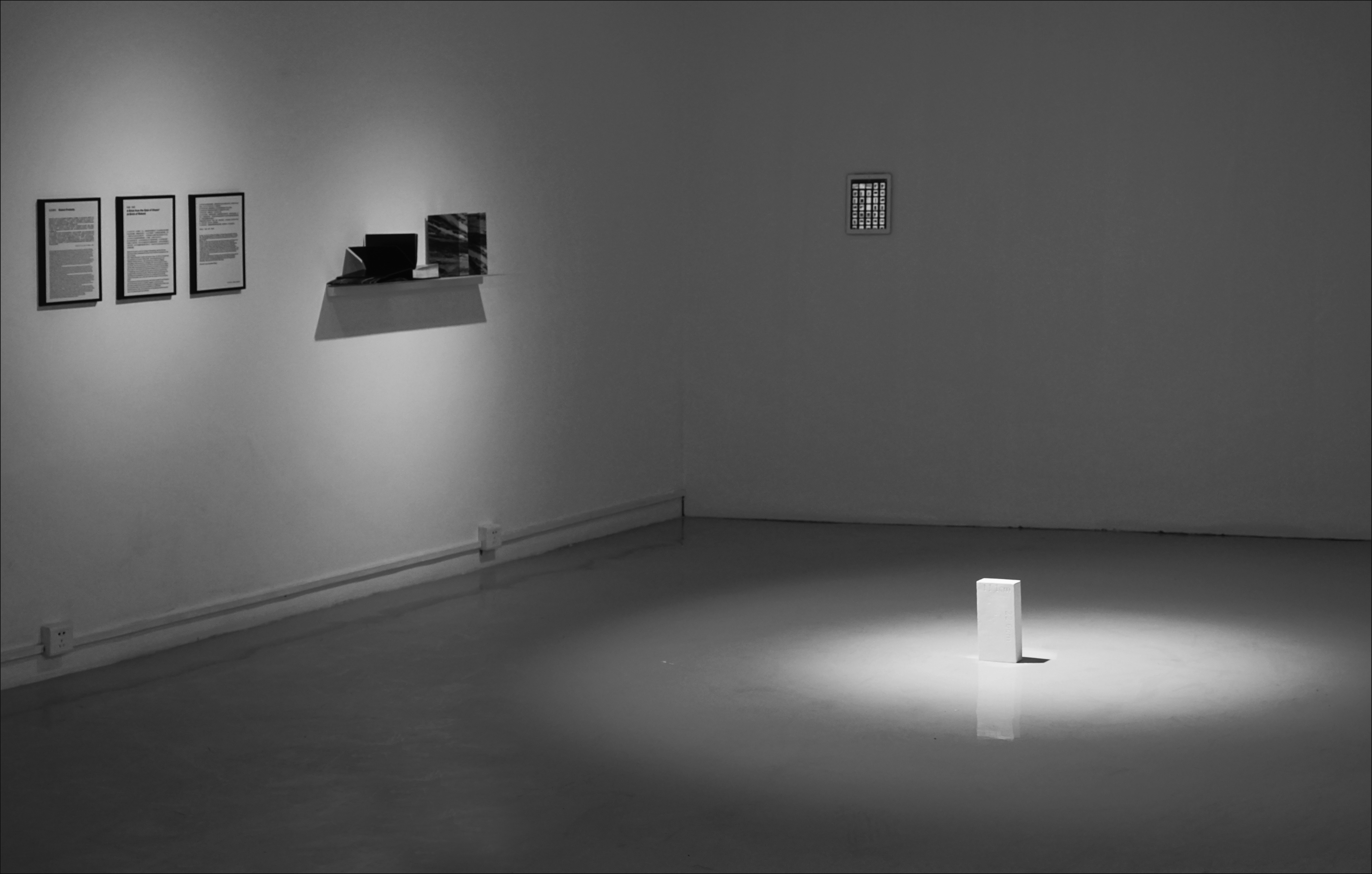

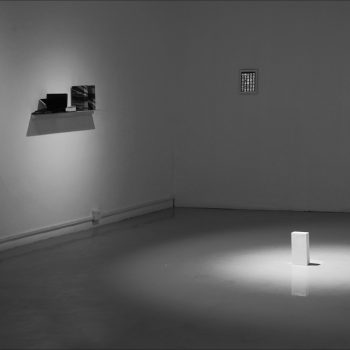

(JX): Your 2013 work, Send For You was about this, right? About how intellectuals have to tip-toe around commercial imperatives of power, especially those put forth by agencies who used to be the underdogs? When those who were once oppressed rise into power, you have to keep your distance. I think this is a really interesting piece, a lot like something Monty Python (exemplary of British black (dark) humor) would do. In the 1940’s Xinhua Daily gave voice to the governing body’s call for democracy, to do away with a single party government. You could say that was what China wanted at that time. In your piece, people could casually walk around with one of your copies of that newspaper. It was a kind of spatial-temporal displacement, an unimaginable action. What was really farcical about it was that the contents of those pages are forbidden today in China, although they were produced by the very party, at that time the opposition, who are in power today. The performative and installation aspects of the newspaper and printing machine are not apparent at first. It doesn’t have the farcical or over-bearing air of a Monty Python skit, but if you think about it all, the “New” (Translator’s note: “Xin” in “Xinhua” translates as “New”) in the title of the newspaper is absurd and totally revealing. A force which once opposed those in power becomes the very power it opposed. What is the relationship between power and truth?

(LYZ): It’s hard to tell a lot of the time, there are people involved who’ve been won over by fancy rhetoric and led about by promises. Also, what you’re dealing with is an organization the internal structure of which is highly secretive. Perhaps you have to pass through all the trials and difficulty, trace things back to their very beginnings. Only then can you gain an overall sense of what’s transpired. We’ve discarded the opinions and opportunism laid out in Xinhua Daily in the 1940’s, never mind the conspiracies or what they had in mind, all the theories and so forth. These things have all become what we know today as “sensitive topics”. The discourses in these pages give off a “testimonial” air. Really, every force that butts up against strong power and authority has the potential to become that very power and authority. It’s only when authority has a system of checks and balances in place that it can tend towards goodness. Power has never existed within the realm of truth. Truth is just some sort of illusion manufactured by those in power to control the masses. As far as the artist is concerned, this whole reality is omnipresent. You may object to it, but it doesn’t take a lot of virtue or reason to see what’s really going on.

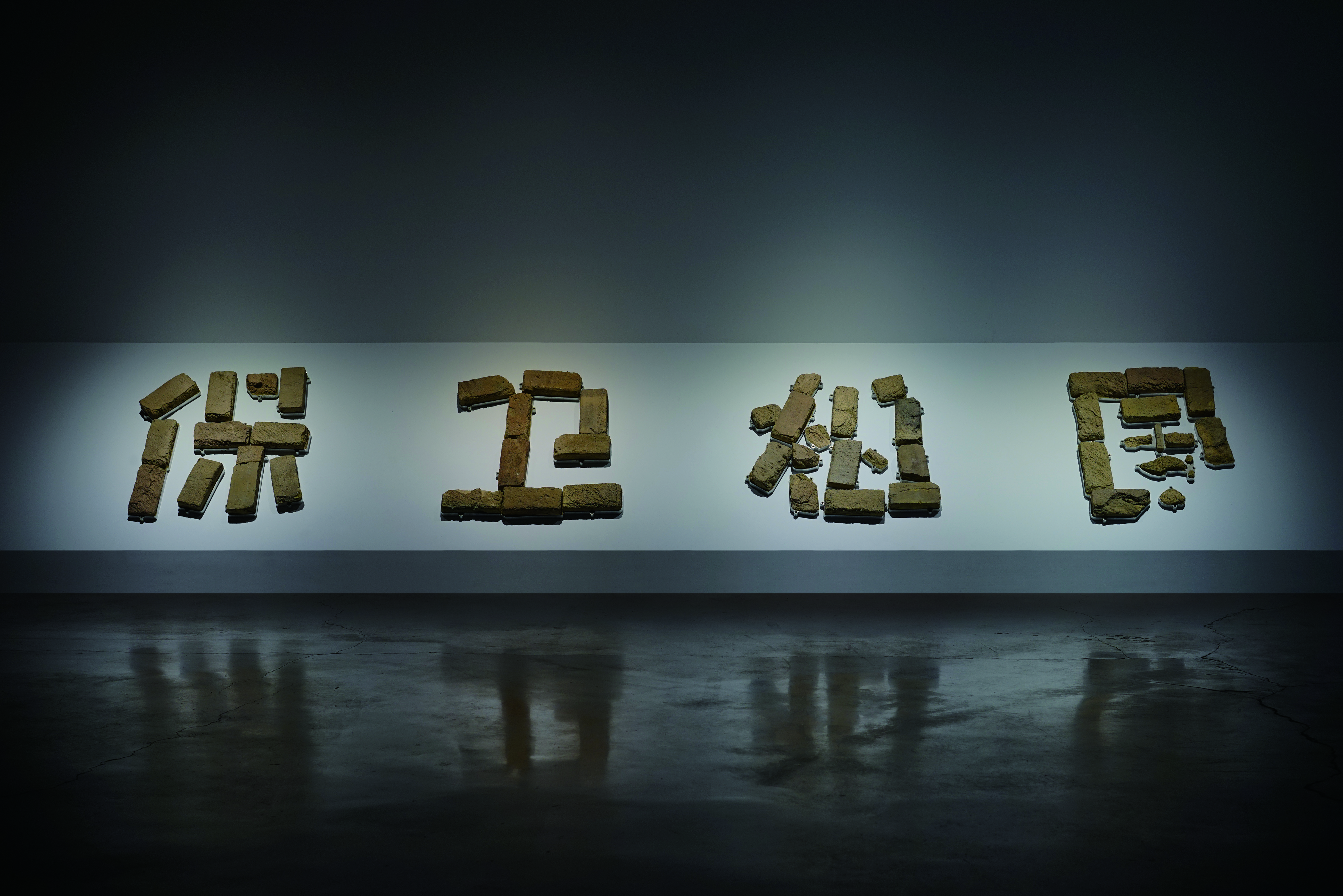

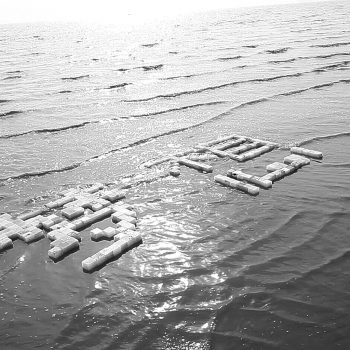

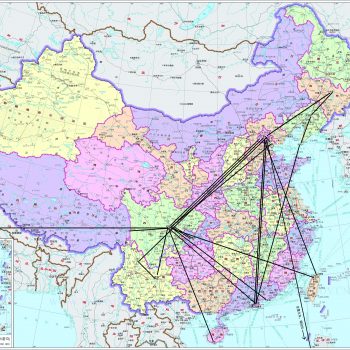

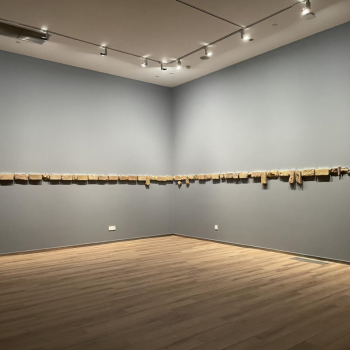

(JX): In your artwork Brick Relay, would you say that on “Wechat and Weibo online you can see some of this plain-speak, some of these naturally arising utterances and writings put out there by the brave and imaginative”? This is a multi-media interactive piece that I’d say hovers between virtual and real societies, a “flash mob” performance artwork. Flash mobs always catch us off guard, becoming a kind of resistance art, like Occupy Wallstreet, which is a perfect example. Those resisting often use a common symbol to form a common identity, like they’ll all wear an orange scarf when appearing in a public space. This kind of symbol in your artwork is a brick. Brick Relay doesn’t appear in an actual public square, it’s never covered by the media or seen by the public, but it’s secret lies in a crowd of people “publicly” disseminating it. It’s social, it’s public, but the masses don’t see its movements.

(LYZ): You mention flash mobs, and this makes me think of the graffiti movement in 1970’s New York, what Baudrillard explains as “without a target, ideology, or semiotic level of content, the graffiti movement is just a primitive cultural process assaulting the system, attacking the ruling order’s clear and obvious political sensibilities.” Actually, in China, these words like “assault” and “resistance” are weak and exaggerated. The problem at hand becomes more and more serious, and all questions end up in the political arena. It’s like one big hot plate that extends limitlessly in every direction, exerting absolute power, and this is the “core issue”. In China, the internet is the only real “public domain”, where you can get to the core of a question, discuss something thoroughly. It’s a relatively free arena in which to express one’s views, and this is changing the manner in which we talk about issues. I believe that every little upgrade will result ultimately in something very different than before. If we want to establish a different system, we first have to find and root out all the seeds sewn into us by the old system. Brick Relay was just a starting point. Over the past four years during which the brick has been passed along, I’ve just been the scribe, recording what each and every person who received the brick did with it. I can never predict how things will end up, and this is what’s interesting.

(JX): Exactly. Evolution is better than revolution. It’s better in terms of setting up future development. But everything’s got to be taken in the context of a specific time and culture. Of course, beside differences between China and the west, and differences in government systems, there’s also difference between time periods. Take Joseph Beuys for example. His ideas of “social sculpture” and that “everyone’s an artist” are revolutionary and avant-garde. But these ideas and expressions have lost their appeal today, they ring empty. In the west, contemporary art seems more fashionable than it’s ever been, more progressive than ever. But in actuality, a lot of artists are just blowing smoke. Neo-cons have taken over the art world. There are museums all over the place, and art is in cohorts with the banking industry, as something to show off. Art is a masses entertainment, some secular religion. This is exactly how art has been effaced. The value of art lies in its negation, in the ways that it provokes discussion and gives hope for the world’s future. So it’s all inharmonious, it’s all been dispersed or co-opted by western capitalism. This is how Chinese art has the potential to be more powerful, vital, bigger than western art.

(LYZ): Capitalism has the ability to consume everything. That’s why skeptical or cynical artists have a lot of work to do. A lot of the new art coming out can’t be understood with old thinking. Our art theorists and curators are perhaps unable to see that which they haven’t seen before. For example, it’s hard to define the flash mobs you were talking about, or Steve Jobs, Google or Uber…are they art? So, China’s specialty is this, that the bigger the question, the more attention its resolution gets. And we’re living through this. But I don’t want to overvalue the ability of Chinese contemporary art to deal with our present reality. We’re all pretty pessimistic about this. Chinese contemporary art is like some big island floating around, hard to connect up with peoples’ everyday lives. China officially controls pretty much all of the venues, and the exhibited artworks. With all the banality, people’s attitude towards the art they see hasn’t changed over the past thirty years. Chinese people talk about people who were born in the 70’s versus people born in the 80’s and so on, but it’s all the same phase, all past tense.

(JX): As we’ve been socialist for a long time, we don’t have a lot of patience for people who label themselves as “leftist”. “Left” and “right” are complicated concepts in Europe and America, and the political climate there (Trump’s conservatism for example) makes things even more complicated. The right wing are focused on country and one’s own people, populist at heart, and advocate free competition; whereas the left wing is more into internationalism, in taking care of the weak in society. In China, “left” and “right” are reversed, the “left wing” is nationalistic and all about market economy…

(LYZ): Yes, and in China, believing in one’s individual self is “right wing”, where one places a lot of importance upon being strong and righteous. It’s not only the “right wingers” that have suffered in the past, making people feel for them, but “right wing” emphasis on individual freedom and things like a people’s constitutional government are more popular today. What makes people uneasy is that China doesn’t really have a left or right wing, but a mere emphasis upon benefit, a way to survive, with values that are talked about a lot but seldom acted on. There’s been an inclination in European left wing thinking towards social equality, so that we see all kinds of things being said democratically in society. If this were to happen here in China, it would be co-opted by Chinese “left wingers” who’d ignore what’s actually happening these days. It would only make the system more powerful.

JX): Leftist movements which started out in the first half of the 20th century reached their peak world-wide in the 60’s and 70’s. The Berlin Wall came down in 1989, and in the early ‘90’s Eastern Block dispersion signaled the end of history (Francis Fukuyama). Fukuyama predicted in the ‘90’s that free multi-cultural capitalism would be the world trend. Various regions of the world would all gradually grow into broad free capitalist cultures. 25 years later, in reality, things are not quite like Fukuyama predicted. The banking crisis which began in 2007 forced us all to take another look at capitalism. Occupy Wallstreet revived Marxism. The European Union saw a lot of right wing internal opposition. The Greek crisis, especially in the last couple of years with the migrant crisis and anti-terrorism, has really seen nationalism raise its head once again. The Front National in France, the Alternative Party for Germany, and America’s republican presidential candidate Donald Trump are all receiving widespread support in society. The left wing was the extreme reform group in the ‘60’s and ‘70’s, they were avant-garde and progressive. Then when in the ‘80’s liberalism became mainstream, student leaders in the 68’ movement became university professors who then controlled social, cultural and political discourses. At the moment in the West there’s this movement to “affirm one’s identity” (identitär). Now the avant-garde is coming out from the right, not the left. So at present you see that leftist mainstream is becoming suspect as the “conservative” party. In a recent interview in Berlin with Die Zeit magazine, Fukuyama said, “Democracy is not self-affirming, so people are worried.” We see history hasn’t reached any conclusion, that it’s merely rolling onward.

(LYZ): I don’t understand what’s going on in Europe right now. What’s fair somewhere is unfair somewhere else. These choices are always to be made in light of a specific time and place, as politics is a matter of games and compromises. But when it comes to the individual, things are much clearer, one makes a choice one can live with and that’s what works. I believe completely in Fukuyama’s prediction. I’m not saying that once all societies are liberal everything will be resolved, because inevitably, when one issue resolves, another crops up. Whether its Occupy Wallstreet, the rebirth of Marxism, or the re-emergence of conservatism, we are always seeing the old replace the new, on and on, and our kind of relatively authoritarian system is an advanced version, which is why China and the West are facing different “core questions”. They are working on a different version. A lot of Chinese still have a modernist complex, they think there is one resolution in this world to all the problems at hand, and maybe in some regards we’re deeply ensnared in this idea.

(JX): In every time, different societies have their own problems and, right, there is no one panacea for all these ills. There is no magic solution. Maybe if there was some cure for all ills, some truth or aesthetic principle, then art would be worthless. Of course, people are always searching for the “ultimate plan”. Romantics are always trying to approach the divine, which will always remain in the distance. Rilke’s Book of Hours is a classic example of knowing that God is dead, but still seeking. Art is about the image and it’s also about the subjective idea. It’s always transcending reality, which is where it converges on religion.

(LYZ): About the always searching for the “ultimate plan”, this is a universal disease, this anxiety about impermanence, about death and the unknown and so on. People are always searching for something to latch onto. But experience tells us these problems will never be solved once and for all. As we get to know and understand the world better, we come head to head with our own limits, with what we don’t know. Accepting reality, involving oneself in society, these are the prerogatives of art right now, as far as I’m concerned. Nothing holds more reality than the problems at hand. Meaning inheres in interactions between people.

(JX): These days, when art and capital go hand in hand, bombastic art theory is powerless. The 2015 Venice Biennale clearly exhibited the art system’s paradoxes and absurdities. Directing curator Okwui Enwezor made Karl Marx the most dazzling artist there. In the main hall, Marx’s Capital was read aloud, denouncing art market hype. At the same time, this curator took already incredibly successful artists like Andreas Gursky and gave them a huge platform, only increasing their value. And with a totally clear conscience, this curator received huge financial support from David Zwirner, who has the world’s art market in the palm of his hand. The curator used photography and other media to expose the oppression of the working class, but in truth, workers in Europe who manufacture art products only make ten euros an hour, with no benefits. Marx was a selling point and front man for the Venice Biennale. But in actual fact, Marx had absolutely nothing important to do with the art there. This sort of disparity between idea and reality is hugely satirical.

Li Yongzheng (LYZ): The 1968 student movement was the pinnacle of the leftist movement, and it was the dying last moment for metaphysics. Kevin Kelly in his new book The Inevitable says, “In utopia, there are no problems, because utopia could never exist. Every conception of utopia has flaws that could topple the ego.” Marx is doomed to be the signboard and tool for the leftists, everything he stood for is already changed beyond recognition, but they still can’t let him go, because they lack the creativity to find a new hat. It’s not important to pay attention to the Venice Biennale, that’s just one component of the market. It’s a way for new modes of thinking to be co-opted into society’s game, and of course it lags behind. The vitality of a given society determines how fast this wheel turns. When all the exhibitions are just totally cliché, then we’ll know how haggard society is, uncreatively discovering and co-opting thought or any new ability.

(JX): All theories are passé. Art happens and it does so without rules. It’s only afterwards that people are quick to summarize and codify, accreting theory to contain it. Just like language. What is grammar? It’s what happens when common natural expressions are analyzed by linguists after the fact. People don’t speak according to the rules of subject, verb and direct object; to think that is like putting the horse before the cart. How do you see the future of art?

(LYZ): Right. Most of the time people are summarizing things that are happening right now in terms of what we already know and have already experienced, giving us an easy conscience, to reduce anxiety. But this is already one step removed from what’s actually going on. Experience usually moves towards benefit and reducing harm. But artistic choices are precisely the opposite. In terms of the future, I think art circles and professional artists will cease to exist. The new artist will take the initiative to learn new technologies, and more and more people will think and create as artists. The artistic spirit will become a part of their lives. The idea that “Everyone is an artist” will see its day once again

(JX): Mark Twain once said, “Humor is based on tragedy, not happiness.” There is no Humor in the paradise. Additionally, art is a game, a serious game, but still a game. I get the sense that your artworks are very serious and charged with philosophical thought. So how do you see the nature of the art game?

(LYZ): I don’t really understand humor. I think this line by Mark Twain is cold. Didn’t we say earlier that art is scarce? When a large number of people are willing to immerse themselves in levels beneath the surface of stirred up emotions, to get to the deeper level of the story, maybe then amidst the tragedy we’ll have ourselves a brand new game.

2016/11/04

Juan Xu: Independent curator, Art critic, and Director of the German Art Exchange Society